Learn more about Diverticular disease and diverticulitis

Diverticular disease refers to small outpouchings of the wall of the colon. These pockets or ‘tics’, are very common, and can be considered a consequence of wear-and-tear from pressure in the bowel, akin to pot-holes in the road.

In our Western population, diverticular disease is very common – almost like having wrinkles. It is present in 10% of those age 40 and increases to over 50% at age 60. It is believed that our modern diet has a chronic lack of fibre. This results in a less bulky stool, and the bowel then has to work harder and exert higher pressures to move the stool through the colon. Over time, these increased pressures result in the formation of a thick muscular bowel wall, which generates even higher pressures. Eventually, diverticulae, or pockets, form at sites of weakness.

Its confusing. The presence of pockets is called either diverticulosis, diverticulae, and diverticular disease, almost interchangeably. Colloquially, we may call these “tics”. These all mean the same thing and in general, do not cause symptoms at this stage of the disease. Once formed, diverticuli do not disappear and most people suffer no ill-effects or symptoms. Whilst they can’t be repaired, we can aim to prevent their progression.

The usual recommendation for people with diverticular disease is to ensure adequate dietary fibre intake, and most peopple would benefit from the use of a fibre supplement available from the pharmacist or supermarket eg metamucil, benefibe, nulax.

The old advice to avoid grains, seeds or nuts has been dismissed. Consumption of these foods have not been shown in large population studies to prevent problems or complications, thus there is no good evidence that any particular foods should be avoided.

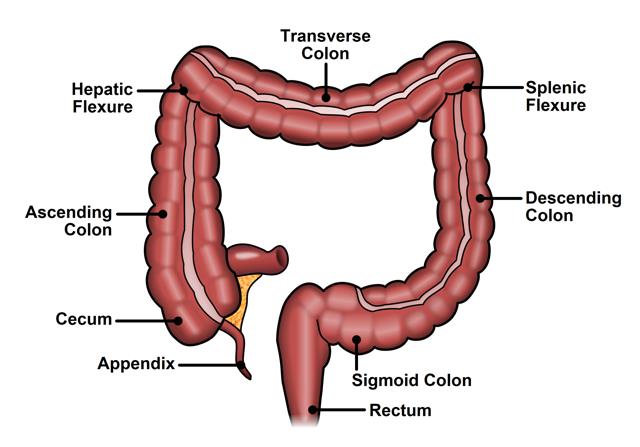

Diverticulitis is the most common complication of diverticular disease and occurs in approximately 15% of patients with diverticulosis. Diverticulitis refers to infection or inflammation associated with one or more of these pockets. This typically causes pain, most often in the left lower abdomen and the pain may be worse with movement. Severe cases are associated with more generalised and severe abdominal pain, fevers, loss of appetite and feeling unwell.

For a long time, we have treated these painful episodes of diverticulitis with antibiotics – but we know now, from high quality evidence, that antibiotics do not make a difference in diverticulitis that is otherwise uncomplicated. That is, there is no difference in the duration or severity of disease, chance of future attacks, chance of complications, or requirement for surgery. Antibiotics are widely used… but changing worldwide practice is like turning a very large truck around, and will happen only slowly!

Uncomplicated diverticulitis may be managed in hospital or at home. New and convincing evidence suggests that straight-forward diverticulitis may not require antibiotics – but this is a change in long-standing tradition that is a little hard to shake! Many doctors still prescribe antibiotics for diverticulitis – it’s going to take time to get the message out.

Antibiotics may still be used depending on the severity of the attack, findings on a CT scan, or if there are associated medical conditions.

Most diverticulitis will settle with time. It can come back though – the chance of a second attack of diverticulitis is about 30%.

After an initial attack of diverticulitis, about 10% of people will suffer from persistent diverticulitis – this can account for a recurrence of symptoms within 4-6 weeks, and is highly predictive of a need for surgery. This persistent inflammation can cause ongoing pain, fatigue, and listlessness. All attacks of diverticulitis for this reason should be followed up with your colorectal surgeon.

Complicated diverticulitis refers to the formation of an abscess, leak or perforation of the bowel. This also results in pain and can have additional signs such as fevers, sweats and becoming more unwell. This may require antibiotics alone, drainage of any abscess, and sometimes emergency surgery. Complicated diverticulitis is normally managed in hospital.

Surgery for diverticulitis is considered for each person differently, and there are no guidelines to allow a “one size fits all” approach. Surgery for diverticular disease is still very common, and one of the most common reasons for a bowel resection by colorectal surgeons.

Surgery may be considered for complicated diverticulitis, repeat attacks, or for symptoms that persist after a first or subsequent attack.

Surgery should be considered after a complicated diverticulitis (such as abscess formation)- the chance of a further problem may be more likely.

Ideally, surgery is done in an elective setting when the inflammation has settled, but is often required more urgently, and sometimes as an emergency.

Generally speaking, surgery aims to remove the worst of the diverticular disease and the affected segment or segments of colon. Surgery usually aims to join the bowel back together, but the individual details will be discussed with your colorectal surgeon.

As a follow-up for diverticulitis, particularly if you’ve never had one before, a colonoscopy is often performed. This is to confirm the presence of diverticular disease and often used as an opportunity to exclude the presence of bowel polyps and even bowel cancers. In uncomplicated diverticulitis, there seems to be no particular increased risk for bowel polyps or cancer, but an increased risk seems to exist after complicated diverticulitis. However – there is no plausible explanation for diverticulitis to be associated with, or indicate an increased risk of bowel cancer. Diverticular disease can be troublesome, but is a benign condition.

Diverticular disease may also may also cause bleeding, although this does not usually occur at the time of pain. Diverticular bleeding is classically dark-red/maroon and may be quite heavy, requiring hospital admission. Approximately 90% of the time, this bleeding will stop, but on occasion requires intervention. Any rectal bleeding warrants investigation by a colorectal surgeon. Each time a diverticular bleed occurs, the chance of a further bleed becomes more likely, thus we try hard to identify the site of bleeding – particularly with recurrent episodes. Treatment of bleeding may be done by a radiological procedure where the bleeding point is blocked off, or embolised, or it may be treated with colonoscopy, and finally, surgery may be required – although surgery for bleeding diverticular disease is a last resort.

If you have had diverticulitis, Dr Morris will discuss what this means, and in view of your history and previous episodes, discuss your treatment strategy moving forward.